Tarot: Play with me

Charles of the beautiful Cartesian mind is trying to explain the game of tarot to me.

I know tarot as a system of divination and more loosely, a calendar for the year. But here, in the South of France, Charles is teaching me the rules of a game he has played for over twenty years. And, he tells me emphatically, it has nothing to do with fortune telling or the seasons.

I wonder if it is any good at getting you out of a plot problem – that elusive spot between the Devil and the deep blue sea that I seem to have written myself into with my latest novel based on Tarot cards. Two sets of cards, I think. Two casts of characters. There might be a way out yet.

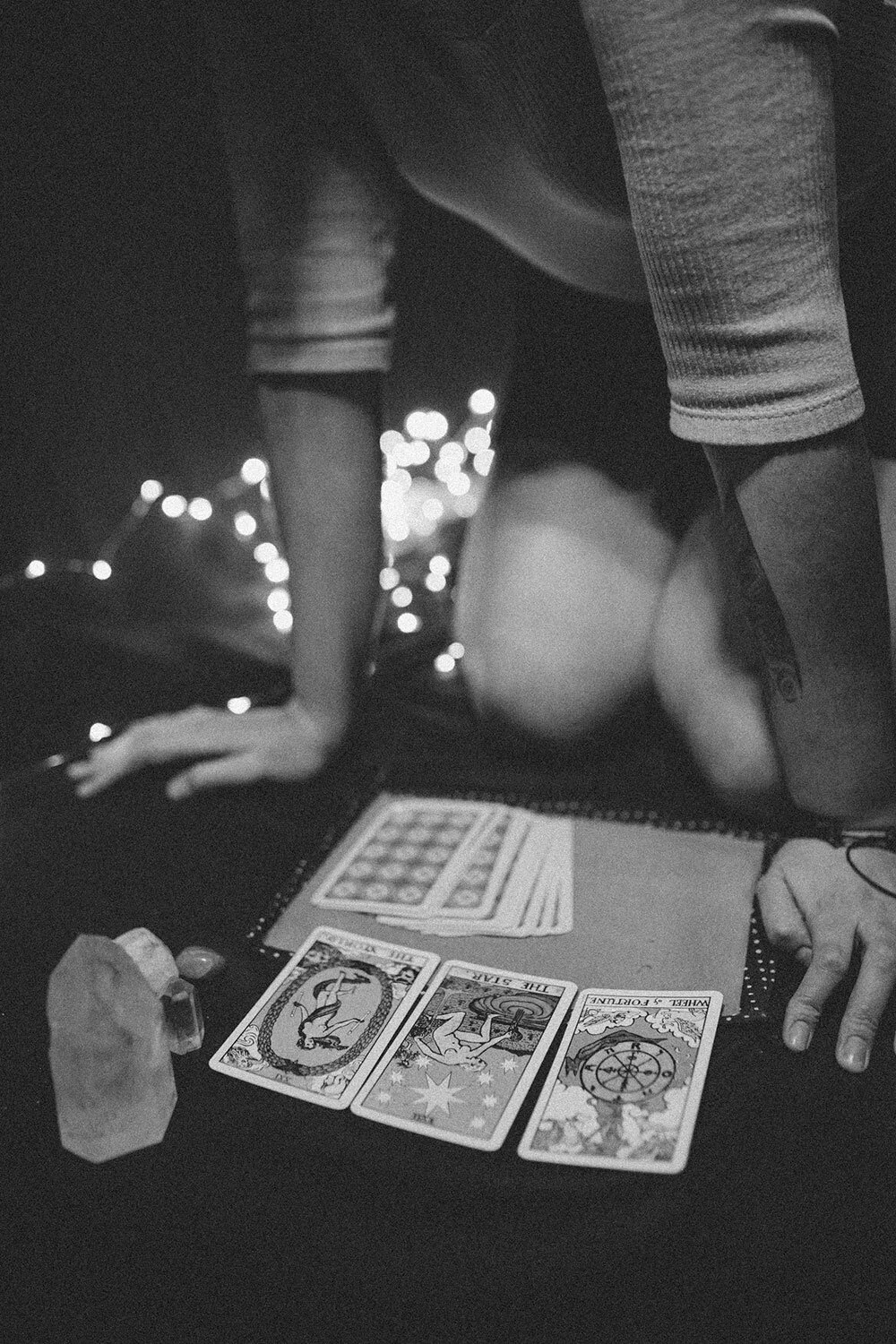

The Tarot cards in my book are from a divinatory deck. This is made up of two Arcanas: the Minor Arcana, which has 56 cards divided into four suits (cups, wands, pentacles and swords) and the Major Arcana, made up of 22 cards, all of which are more important than any card from the Minor Arcana. The Major Arcana begins with the Fool and passes through different stages of human development embracing Mother, Father, Lover, Death and the Devil on the way. The cards are archetypes, of a sort. Impulses, conscious and unconscious, that drive us on.

There are only three important cards in Charles’ deck. Three “trump” cards, if you will, that are more important than any other - the Fool, the Magician and the World – and they don’t have names, only numbers, and the Fool doesn’t even have that. The Fool has a small black star in each corner of his card. The Magician, a big fat one and the World, 21. In my deck they represent desire, new beginnings and the end. Imagine a world where Death is really on an equal footing with Love. Or, a Fool holds more power than an Empress.

Charles’ Death card, 13, is as powerless as the one that follows it. The images on his deck of cards show a group of well-dressed, upper class people at a soiree of sorts, and underneath, as a kind of mirror image, more ordinary people at a market. It’s a far cry from the armored skeleton knight on a white stallion marching across the card I know.

In the game, Charles tells me, you play with a contract and a partner and the aim is to win as many hands as you can. I suppose divinatory Tarot is the same – in a way. Getting what we want, is why we consult cards in the first place. Only things are not always what they seem in that world: the King of Cups declaring his undying love will not last long if The Devil sits under him or The Tower falls in front of him.

Charles ropes in other houseguests to play a hand of Tarot. Well, Charles plays two hands explaining what we should or could do all the way through. Of course, he wins. By chance, Charles and his partner hold the Magician, the World and the Fool between them. . . Even to my green eyes, it is hard to lose if you hold all three trumps in a deck.

Fool, Magician and World. It almost sounds like a mantra. I study the cards again. The Fool is the same whichever way you look at him, but not the Magician who in the mirror illustrations on the card turns from Fool flirting with a pretty girl to Pierrot being scolded by a Lord. And what does this game place on the World card but images of a military parade (with a Fool in the ranks) and a ball where, perhaps, all people become fools under the influence of alcohol and music.

Given the choice, I would build my World away from Fools with only Magicians for friends. I look out at the heart of the French countryside. I would build it here, in fact, under this huge blue sky, next to a stream surrounded by sheep, small rabbits and wild thyme. In this perfect setting, I would let loose the archetypes of the Major Arcana from my deck – just to see how fairly they would play a game of Tarot with people who don’t wish to consult them at all. And, while those Archetypes were happily distracted, I would consult the three trump cards of Charles’ game – the Fool, the Magician and the World and ask if I were to trap a Devil from a different deck, if they would be willing to help me.